How do we know our perception of the world is what we believe it to be?

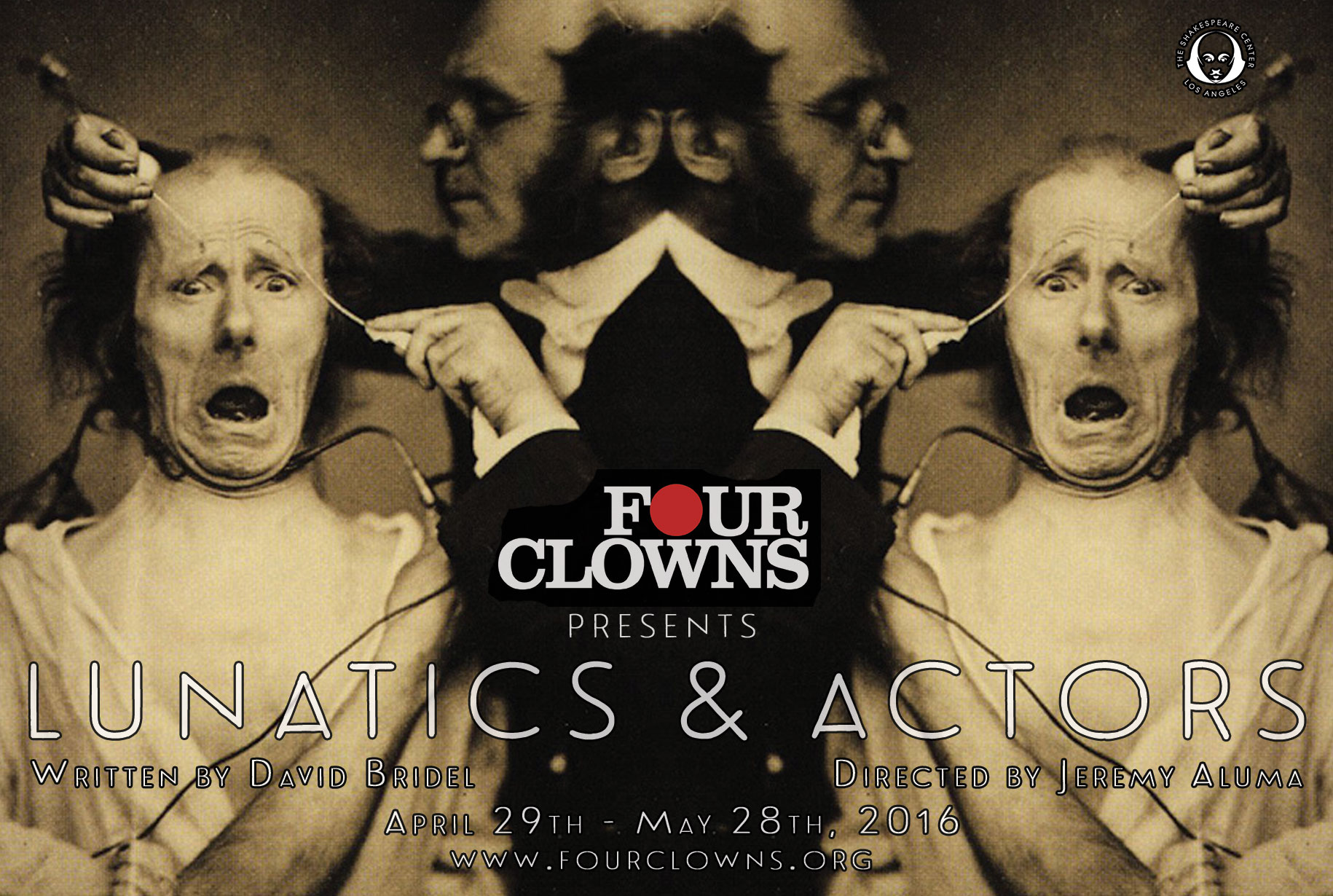

This deep question is ultimately at the heart of the new production from Four Clowns at The Shakespeare Center of Los Angeles, Lunatics and Actors, written by David Bridel and directed by Jeremy Aluma. Lunatics & Actors explores the question of emotional authenticity, through a descent into the real-life obsessions of Dr. Guillaume-Benjamin-Amand Duchenne du Loulogne. du Loulogne was a French neurologist who greatly advanced the science of electrophysiology. Duchenne’s monograph, Mécanisme de la physionomie humaine – also illustrated prominently by his photographs – was the first study on the physiology of emotion and was seminal to Darwin’s later work. Duchenne also wanted to determine how the muscles in the human face produce facial expressions that Duchenne believed to be directly linked to the soul of man. Duchenne is known, in particular, for the way he triggered muscular contractions with electrical probes, recording the resulting distorted and often grotesque expressions with the recently invented camera. The images that Four Clowns used in their poster for the program are literally of Duchenne performing facial electro-stimulation.

In Lunatics & Actors, Duchenne (Thaddeus Shafer (FB; FB (page))) is presenting the audience with a simple question: what is authentic emotion? Can a highly skilled trained actor produce authentic emotion? Can the skills of the actor surpass the real emotion induced through electrostimulation? In asking these questions, the production induces a different set of question in the audience. Namely, it raises the question of whether any of the emotions that we might see on stage or screen are real, or even realistic portrayal. Is the entire history of theatrical entertainment just an artifice, a facade of fake emotion? If it is, are we better off going out and experiencing real emotion?

The way that Duchenne does that is to create a challenge: knowing that he is in Los Angeles and the audience is filled with actors, he selects three actors from the audience to test against three lunatics from his asylum. The question: between the actor and the lunatic, who can portray the most authentic emotion. He begins by interviewing the actors to find the most skilled amongst them, based on training, technique, experience, and recognition. At our performance we had three actors, whose names I cannot currently remember. There were various levels of technique and experience, ranging from students to one who had won a few local awards and had toured with a Shakespeare troupe. The doctor selected the most experienced candidate, and we were off.

The doctor then introduced us to his three lunatics: Bon-Bon (Tyler Bremer), Fifi (Alexis Jones), and Pepe (Andrew Eldredge). Not being an expert in neuropsychology, I can’t quite described their maladies. Externally, Bon-Bon seemed to be driven for treats, but otherwise pliant and withdrawn. Fifi seemed shell-shocked; she wanted treats but never got them. Pepe was energetic and strange, almost prone to violence. All were in straightjackets.

The doctor then proceeded to request the selected actor to portray a series of emotions, which in many cases seemed to confuse or befuddle him based on his experience. He then used electroshock on his selected lunatic, and induced the requested emotion. The audience was then asked which was the most authentic emotion. In most cases, it appeared to this audience member that the lunatics gave the better performance. It seemed that way to our selected actor as well, as he got more and more incensed.

Things, well, things degenerated from there.

To describe more of the story might give away some of the twists and turns, so I’ll defer doing so. But the experience, as noted above, explored electroshock therapy, and its ability to make its subjects do whatever the authority figure asks them to do, and to believe whatever the authority figure wants them to believe. One review I encountered writing this up referred to this as gaslighting on stage. Reviewing the definition of the term, I would say that is accurate. As such, I would note that this performance could potentially be triggery (i.e., TRIGGER WARNING) to those troubled by gaslighting simulations or situations, or those who have undergone electroshock therapy. But I think the ultimate question the gaslighting results asked is a real one — and a significant one — are the emotions and beliefs we see something that we should believe, and who is really responsible for those emotions. Is the fear induced by electroshock (for example) the same as real fear for a situation? Is what is perceived as real by the lunatic or actor the same as a real-life experience? For actors, what is a realistic performance?

I don’t think these questions are easy one, but I think the discussion of them can be an interesting discussion. However, the path to get to the questions can be a dark and disturbing one; perhaps one that is not for everyone.

But this is a Four Clowns production, you say. Where are the clowns? Wikipedia says the following about clowns: “The comedy that clowns perform is usually in the role of a fool whose everyday actions and tasks become extraordinary—and for whom the ridiculous, for a short while, becomes ordinary.” That is certainly true in this production. The style of questioning of the actors by Duchenne is clearly ridiculous, and the answers (and his reactions) to the questions becomes hilarious. The performances of the lunatics: they are certainly foolish and become extraordinary in the transformation of their madness. So while this is not your traditional clowning — and certainly not the style of clowning we saw in Four Clowns’ recent Hamlet — it is one of the funniest shows I’ve seen in a while.

Other reviewers I’ve read have been seemingly insulted by the premise of the show. The aforementioned “gaslighting” review said ” In essence it is an experiment in acting versus physical forced mind control, the gas lighting of an artist to a mere puppet or shadow of the real.” and it went on to state “What the play is lacking is the realization that the physical manifestation of an expression could be separate from the actual feeling. If anything this play can be the center piece of a lively discourse for actors of the conflicting acting schools of thought…”. Now, I’m not an actor. I’ve never claimed to be an actor, and I’m envious of those that can inhabit other characters. I’m a cybersecurity specialist — an engineer — who loves watching theatre. To me, it raised the interesting question of the artifice of what we see, and whether our senses can really tell us anything authentic about the world. It emphasized the importance of experience over detached observation. As such, the play remains a centerpiece for lively discussion, but perhaps not the discussion that an actor might have (who would feel their craft had been insulted by the question).

I should note that the play does not appear to be an accurate representation of the works of Dr. Duchenne. Then again, it doesn’t claim to do so: it is a fictional play, not an autobiography.

It somehow seems inauthentic to say this (at this point), but what makes this play works so well is the performance of the actors, and the qualities and emotions that the director draws out of them. Whether they were real or not, they were transmitted to the audience and they felt real. All of the actors were excellent, but I’ll particularly call out Thaddeus Shafer (FB; FB (page))’s Duchenne. He was hilarious in his questioning of the actors and his responses to their responses. How much of this was scripted vs. improvised is unknown to me. It was funny to watch. He also handled the dark side and the descent of Duchenne quite well.

The portrayal of the three lunatics, Bon-Bon (Tyler Bremer), Fifi (Alexis Jones), and Pepe (Andrew Eldredge), was also quite strong. The transition between lunatic and sane emotion was quite startling, and seemingly believable. As such, it was a remarkable performance.

Lastly, there was the actor that was selected at our show. For an unprepared actor drawn from the audience, he was great. In particular, he was remarkable as the show descended into madness and gaslighting. He’s lucky he remembered his lines from his past shows.

Turning now to the production aspects: One of the remarkable things about Four Clowns productions is their set design. Fred Kinney, who designed the set here, did a great job of creating the industrial madhouse feel. There was sheetrock hung by galvanized steel plumbers tape. There was open 2×4 woodwork. There were industrial power boxes, seemingly wired to control the industrial style lighting. A remarkably creepy feel, augmented by the lighting from Azra King-Abadi and the well-timed sound effects from Kate Fechtig, who did the sound design. The combination was…. realistic and creepy. Kinney also did the properties (under the control of Nicole Mercs, propmistress). The electroshock apparatus had a wonderful steampunk-ish feel to them with loads of exposed brass, cords, and old-style incandescent lighting. That, combined with the chairs and other props, increased the uneasiness feeling substantially. I was also intrigued by Duchenne’s glasses. Elena Flores provided the costume design, which was equivalently creepy with blood-splattered straight-jackets and Victorian dresses and suit-pants. Rounding out the production credits were: Matt MacCready [Technical Director]; Amaka Izuchi [Assistant Director]; Ashley Jo Navarro [Stage Manager], and David Anis [Producer].

The publicity material for the show notes that this is the last collaboration between David Bridel and Jeremy Aluma for a while. Bridel continues in his academic positions as USC, where he directs the MFA in Acting and is Interim Dean of the School of Dramatic Arts. Aluma is off to Chi-town for grad school for an MFA in Directing. Having met Jeremy a few times through Four Clowns, I know he will be great and I wish him well in his new city. Hopefully, he’ll direct some theatre there that he can move to Los Angeles.

– Daniel Faigin